I can’t claim to care about open access education and not say anything about the recent events involving public library funding, so here I go. If you haven’t been paying attention to your local public library, you’re probably paying instead for subscriptions or services that you don’t need, unaware that libraries offer the same thing for free. Or, if you’re not overpaying for something, you’re needlessly going without something. Modern public libraries provide the public with much more than books and print media. They’re intentional about tending to your entire wellbeing. Your local one most likely grants you free access to ebooks, audiobooks, movies, music, accessibility aids, education resources for adults, social services, and a surprising range of other items that aren’t necessarily media.

As constructive and valuable as all of that sounds, public libraries desperately need support these days. Various news reports from 2023 and earlier have put a spotlight on public libraries facing the challenge of defunding. What I’ll do here is provide you with the history of the public library as a public good. Then I’ll explain why it’s an unwise idea to play takebacks with funding for something so essential.

Why public libraries provide care: An estimation of your worth

American optimism played a major role in the rise of public libraries, and it’s why public libraries feel a responsibility to engage in societal uplift today. In 2001, librarian Nancy Kranich compiled an anthology of essays titled Libraries & Democracy: The Cornerstones of Liberty. [1] The essays support the idea that American public libraries are tools for cultivating a democratic society and that they naturally adapt over time to meet society’s changing needs. Two widely regarded history books, Foundations Of The Public Library by Jesse Shera and Arsenals of a Democratic Culture by Sidney Ditzion, are cited throughout the Kranich anthology. [2] [3] In their books, both Shera and Ditzion argue that the public library was a means for the American public to achieve its optimal, most enlightened state as a body politic. They both describe library history as follows: as America flourished intellectually and materially, its leaders, eager to accelerate progress, promoted open education and helped libraries evolve from predominantly private to predominantly public institutions.

I mentioned public libraries’ adapting over time to society’s changing needs. The public library’s creation in the first place was itself an adaptation. Private book collections of the 1700s, typically only accessible to the well-resourced or the intelligentsia, were gradually replaced with book depositories accessible to a broader group of men. [i] Opinion leaders of the time decided that as much of the American electorate as possible required as much education as it could attain to ensure the best possible governance for the country. They began to see high-access, quality education as necessary for collective survival, and they believed that, to achieve it, there needed to be an institution that was supplementary to the public school.

Since the emergence of the first municipally-funded libraries of the early 1800s, the definition of public library had been subject to different interpretations, but one essay in the Kranich anthology identifies the 1960s War on Poverty as the impetus for the most significant reimagining of what it means to provide public library services. [4] Motivated by the Library Services and Construction Act of 1964, libraries aspired beyond providing books and other literary materials, and they sought funding for new projects. Library professionals began to discuss the feasibility of implementing early childhood development programs, job preparation programs, and campaigns to distribute information about wage laws. [5]

Public libraries of the current century continue to rework their understanding of how to best serve the public. In 2016, the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) came up with a framework to measure a library’s or museum’s contribution to the overall social wellbeing of its community. The report that introduced the framework, titled “Strengthening Networks, Sparking Change,” proposed that a library’s value can be measured in terms of how it contributes to a community’s physical and mental health, availability of cultural resources, and other dimensions of wellbeing. [6] [ii] By 2021, IMLS published a new study, titled “Understanding the Social Wellbeing Impacts of the Nation’s Libraries and Museums,” to gauge exactly how well libraries and museums contribute to social wellbeing. [7] In the 2021 study, researchers found that public libraries and museums contribute to community health, school effectiveness, institutional connection, and cultural opportunity. [8] A modern public library might easily offer things like free tutoring, podcast equipment that’s free to use, health and wellness classes, and in-house social workers.

For what it’s worth: Offerings of the modern public library

The most prominently featured resources on a public library’s website are its free digital services like ebooks, audiobooks, video streaming, and music streaming. Popular services include

- Libby for ebooks and audiobooks: OverDrive, the marketplace through which libraries obtain the license to offer their patrons Libby and Kanopy, claims that Libby is used by 22,000 public libraries worldwide. [9] A feature article by the Wall Street Journal claims that 90% of North American public libraries use Libby. [10] If you’re in the US, your local public library is highly likely to at least grant you access to Libby.

- Kanopy for movies and television: David Burleigh, OverDrive’s Director of Corporate Outreach and Development, says that Kanopy is used by 7,500 public libraries worldwide. [iii]

- Freegal for music: Freegal works with around 500 libraries, public and otherwise, specifically in the US. [iv]

- Hoopla for all of the aforementioned services: Hoopla works with around 2,918 libraries, public and otherwise, in the US.

To give you a bit of perspective, IMLS identifies 9,248 total public library entities in the US as of their 2022 Public Libraries Survey. [11] [12] [13] Though I’ve highlighted Kanopy, Freegal, and Hoopla to suggest that they’re all popular, the numbers indicate that the majority of US public library entities don’t provide those services. That’s because the majority of US public libraries, actually 76% of them, are small libraries that serve populations of less than 25,000 people. [v] They consequently have less than larger libraries have to spend on collections and electronic materials. But you’re not necessarily barred from accessing those services if a smaller library is nearer to your home than a larger one.

Residing within a certain county or a certain state often makes you eligible for membership at a library serving a larger area, which in turn gives you access to the larger library’s services. For example, you might be a member of San Ildefonso Pueblo Library in New Mexico because it’s within your community and convenient for studying on most days. If you want to try Hoopla, but your library doesn’t offer it, you could get a second library card from New Mexico State Library and access the service that way. Note that you can often use libraries’ digital services beyond physical library locations as long as you have your library card credentials and internet access.

Less-advertised public library benefits include

- access to business data and scholarly journal databases that would otherwise be expensive: A public library might grant you free access to Morningstar for investment research, Academic Search Premier or something similar for academic research, or a subscription-based newspaper like the New York Times.

- free resources for personal and professional development: Free courses offered either directly through the library or virtually through a third party are likely to cover subjects like language, digital literacy, skill building, and many others. Your library might even give you access to free tutoring.

- accessibility aids: Many libraries can provide their patrons with assistive technology like book reading devices specifically designed for people with disabilities.

- libraries of things: The term library of things describes a materials lending program where the materials being lent are not the traditional ones, like literary or archival materials, that people typically expect to find at a library. A library of things can lend its patrons items like tools, musical instruments, electronics, equipment, and beyond. [14] Libraries have lent nontraditional materials since the 1900s, [15] but the concept now known as the library of things really crystallized during the 2010s. [vi] Shareable, which describes itself as a news and action hub focused on the solidarity economy, [16] [17] claims that around 400 library of things programs exist around the world as of 2019. [18] [19] [20] [vii]

- health and wellness benefits: According to the IMLS, many modern public libraries offer health benefits in the forms of information resources, classes, and workshops.

- social services: Public libraries provide social services by connecting community members in need to the right resources. They can do this by providing referrals to third-party social service providers or by taking direct action themselves. One of the most innovative examples of a social service provided by a library is the mobile showers program offered by the Las Vegas-Clark County Library District. [21] [22] Another concept gaining recent attention is libraries’ acquiring social workers to serve library patrons in-house. The blog Whole Person Librarianship currently shows that there are 297 distinct library locations with social workers in the United States. [23] [viii]

- third places: A third place is anyplace that you frequent outside of your home (your first place) or work (your second place). Or it could be a place that you frequent outside of home or school. The authors of the 2021 IMLS study found that libraries function as third places for their communities. [24] Research from other organizations supports this idea. In a 2016 Pew Research Center survey of 1,601 Americans ages 16 and older, 66% of respondents expressed that the closing of a public library would have a major impact on their community. [25] The National Library of Medicine (NLM) claims that the public library is a place where people experiencing vulnerability go for heat or air conditioning, water, and general safety. [26]

Especially for people experiencing vulnerability, libraries serve as a particularly valuable resource from which to receive all of the benefits mentioned. This is because libraries are often some of the few places—if not the only places—where vulnerable people can go. The NLM and the IMLS both mention this. [27] In his book Palaces for the People, sociologist Eric Klinenberg claims that he witnessed the library’s role as a last refuge for elderly and unhoused people while conducting first-hand research in New York City. [28] For people most in need, access to a public library can determine what kinds of lifelines are available to them.

Defunding = your devaluation

The 2021 IMLS study mentions that public libraries frequently encounter community members in severe states of need, so wanting to address community needs is a matter of course for them. The study also acknowledges that public libraries’ reliance on government funding undoubtedly influences them to position themselves as community benefits and evoke community in their value propositions.

Even with those factors considered, American optimism deserves a good share of the credit for the modern public library’s attention to community. A spirit of optimism is what transformed libraries from being mostly private to mostly public and allowed for the forward-thinking library programs that sprang out of the 1960s. At the same time that the spirit of optimism was having an effect on libraries, it was working its way into other parts of American life, like early childhood development.

Social historian Maris Vinovskis describes the state of children’s education just before and during the War on Poverty in his book The Birth of Head Start. [29] As noted in the book, there was a change in mindset among the researchers of that time, who became more confident that long-term poverty could be eliminated by education. Also, new studies challenged previously-held beliefs about the fixedness of IQ. [30] Policymakers applied what they learned to the American public with newfound enthusiasm, and improving the lives of struggling people was presented as a more hopeful and worthy cause than before. The Birth of Head Start even provides a quote from Edward Zigler, a renowned psychologist and Head Start champion, wherein Zigler reasons that meals and medicine for children can be better uses of government funds than military weapons, even if the meals and medicine don’t ultimately result in the achievement of some socioeconomic performance benchmark. [31] [ix]

I see parallels between the War on Poverty’s rehabilitative sentiments and the public library’s modern-day focus on care. These parallels indicate belief in human potential and willingness to invest in that potential. Recent stories about abandoning support for public libraries, then, demonstrate a lack of regard for human potential. Contrast the goodwill of Zigler’s mindset with the target trained on library dollars over the past few years.

News coverage about public library defunding spans across multiple states, and articles on the subject mention that defunding is being considered in many places around the country. [32] [33] [34] [35] Much of the defunding talk has been traced back to an ultimate desire to ban certain books held by the libraries. [x] But there’s also the case of New York City, where the idea to cut library spending was just a matter of how priorities were set.

There are some obvious reasons why defunding is risky. A library is often the sole institution in its area holding archival materials of unique historical or cultural significance. Think about maps or genealogical records that are specific to a very regional or low-population area, and think about the fate of those materials if the libraries or museums preserving them suddenly dissolve.

And while books, movies, and music can now be accessed online, the modern public library enables you to consume some of those same items online at no cost. Libraries even grant you free access to resources like scholarly journal databases, newspapers, and real business data that would otherwise cost you subscription fees.

Another concern is the loss of the social wellbeing benefits mentioned by the IMLS and other publications. Readiness to forfeit those benefits speaks to lack of regard for people. What if the head of your municipality decides—or your neighbors even vote—to financially starve the local library that functions as the most reliable source of internet access for the rural area where you live? What if the library has its hours cut or has to operate for fewer days, but it serves as a place where the elderly or the financially-strapped go to escape harsh heat or cold? What if it’s just a safe place for young people to socialize, but its future is now in question? Would losing so much, in addition to free media and free databases, engender warm fuzzy feelings? Would it make you feel like your community was seen as worthy or containing any potential? Or would you be a little bit offended? What if you’re one of the people on the other side, pushing for defunding? Have you fully considered the implications of that?

Effective action

If you’re in support of your local public library, and its funding ever becomes uncertain, a way back to stability is possible. New York City, briefly referenced earlier, actually recently provided us all with a seemingly solid playbook for this. Early in calendar year 2024, NYC Mayor Eric Adams revealed his intention to cut the city’s public library budget by $58.3 million for fiscal year (FY) 2025. By that time, funding expected for FY 2024 had already been cut by $23.6 million, which swiftly resulted in reduced weekend hours for all three of the city’s public library systems. Library advocates, not wanting to roll over and let the FY 2025 cuts happen, organized a campaign to pressure a reversal. Advocates included public library heads, members of New York City Council, and public figures in pop culture and elsewhere. [36] They coordinated messages to the mayor, [37] testified at the city’s budget hearing, [38] and held rallies; [39] and it was all surprisingly effective. By the end of June 2024, the $58.3 million that got cut was restored for FY 2025.

Now, keep in mind. NYC is a popular place, which in large part explains the attention the campaign received. I’m not presenting the city’s results as being completely replicable by anywhere else, but I do think the story has inspirational value. And note that the tactics employed for the campaign, like city council testimonies, letter drives, and rallies, are things you’ve heard of before. So you don’t need abounding imagination to at least start doing something on behalf of your library. Opt for helpfulness over hopelessness, and think of lending your voice as the least you can do. Be the first soundwave in your community, and you never know how you might be amplified.

That’s all I wanted to say. Put this issue on your radar if it’s not already.

[i] In Foundations of the Public Library, Jesse Shera elaborates on this progression. He describes a spirit of ambition burgeoning in the New England region during the formative years of the US, spurring men to pursue self-education as a means of self-perfection. The election of President Andrew Jackson in 1828 was reportedly a marker in history reflecting the rise of American optimism, because it made the presidency seem more attainable to young white men. Specific language conveying the attitude at this time describes men as capable of becoming “more and more endowed with divinity” and “more god-like” in character. [40] If only they could read more, they could tap into their higher selves. As explained by Shera, this attitude was a driving force motivating Americans to establish more spaces where common folk could access books.

[ii] Social wellbeing can be described as a multidimensional approach to assessing the wellness of a group of people beyond their economic condition. For the purpose of the IMLS studies, dimensions of social wellbeing include economic wellbeing, economic and ethnic diversity, health, school effectiveness, cultural engagement, housing quality, political voice, the presence of nonprofit organizations and cultural resources, quality of physical environment, and physical security. [41]

[iii] Kanopy’s website currently says that it’s used by 4,000 libraries worldwide, which differs from the 7,500 count provided by David Burleigh via email on May 6, 2024; but the Kanopy page showing 4,000 was last updated on October 21, 2020, according to the website’s sitemap at the time of publishing this post.

[iv] I’ll say more about how I came up with these numbers for Freegal and Hoopla later.

[v] The American Library Association’s (ALA’s) resource guide (archived September 20, 2024) calls attention to the percentage of public libraries that serve populations under 25,000 people, so I’m using that same population size to provide perspective here.

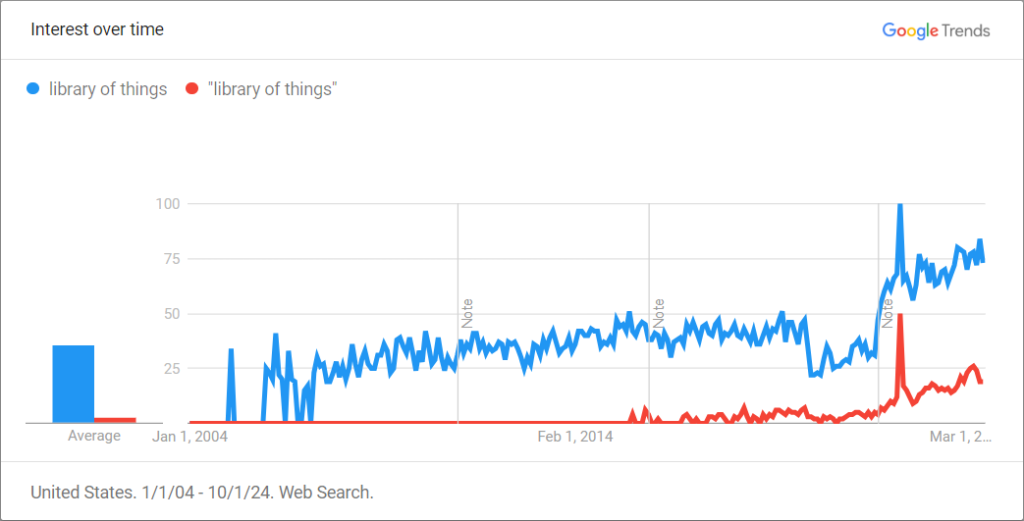

[vi] According to Google Trends, the search term “library of things” only gained interest at specific points in time between 2005 and January 2007. Between January 2007 and December 2021, interest stayed around a midpoint. Since December 2021, interest has climbed upward. As of the date that this post is published, the height of interest in this term occurred in August 2022. Note: The interest measure shown is an index and does not represent the actual number of searches.

[vii] This number seems to be a count provided by a single software vendor, myTurn. [19] [20] myTurn is an asset management software used by libraries and other entities to run their library of things programs. myTurn is also a sponsor (archived September 7, 2024) of Shareable.

[viii] Library social worker Patrick Lloyd, speaking in a webinar hosted by the National Library of Medicine (NLM), cited Whole Person Librarianship as a source for this kind of data in 2022. [42] Whole Person Librarianship is a blog written by librarians Sara Zettervall and Mary Nienow. Lloyd identified around 48 library systems with social workers across the United States as of 2022. The count derived from Whole Person Librarianship’s website is a count of distinct US library locations, which can include multiple branches within library systems.

[ix] “Few of us on the Planning Committee really believed that an eight week summer program could produce many lasting benefits in children’s lives; we certainly didn’t think that a couple of meals a day and some vaccinations could ‘cure’ poverty. But the estimated $18 million price tag for the entire summer Head Start program was about the same as the cost of two fighter bombers at the time. If the nation could spend so much money on a war that was benefitting no one, why couldn’t it spend a fraction of that amount on poor children in Head Start? The program certainly wouldn’t do any harm; it might even do some good.” [31]

[x] I don’t yet have the range to fully participate in the conversation about book content, but many reliable sources are already talking about it. Also, a large part of my argument in this post is that it shouldn’t even matter. Given their willingness and capacity to provide critical services to all members of society, public libraries are too essential to have their funding jeopardized.

References

[1] Kranich, Nancy C. Libraries & Democracy: The Cornerstones of Liberty. Chicago: American Library Association, 2001. Read for free: https://archive.org/details/librariesdemocra0000unse.

[2] Shera, Jesse H. Foundations of the Public Library: The Origins of the Public Library Movement in New England 1629–1855. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1949. Read for free: https://archive.org/details/foundationsofthe012037mbp.

[3] Ditzion, Sidney. Arsenals of a Democratic Culture: A Social History of the American Public Library Movement in New England and the Middle States from 1850 to 1900. Chicago: American Library Association, 1947. Read for free: https://archive.org/details/arsenalsofademoc006465mbp.

[4] McCook, Kathleen de la Peña, “Poverty, Democracy and Public Libraries,” in Libraries & Democracy: The Cornerstones of Liberty, (Chicago: American Library Association, 2001), 31-32. Also see PDF: McCook, Kathleen de la Peña. “Poverty, Democracy and Public Libraries.” University of South Florida School of Information Faculty Publications, 2001, 111 (PDF pages 6-7). https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1110&context=si_facpub.

[5] Drennan, Henry T., Dorothy A. Kittel, and Pauline Winnick. “A Full Range of Weapons.” Library Journal 89 (September 15, 1964): 3266-73 (PDF pages 29-26). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED021882.pdf.

[6] Norton, Michael H., and Emily Dowdall. “Strengthening Networks, Sparking Change: Museums and Libraries as Community Catalysts.” Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2016, 31. https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/publications/documents/community-catalyst-report-january-2017.pdf.

[7] Norton, Michael H., Mark J. Stern, Jonathan Meyers, and Elizabeth DeYoung. “Understanding the Social Wellbeing Impacts of the Nation’s Libraries and Museums.” Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2021. https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/2021-10/swi-report.pdf.

[8] Norton, Stern, Meyers, DeYoung, “Understanding the Social Wellbeing Impacts,” 14.

[9] OverDrive. “Public Libraries Lend One Billion Titles with the Libby Reading App.” January 25, 2023. https://company.overdrive.com/2023/01/25/public-libraries-lend-one-billion-titles-with-the-libby-reading-app/.

[10] Tibken, Shara. “The Money-Saving Power of Your Library Card.” The Wall Street Journal, April 9, 2023. https://www.wsj.com/articles/the-money-saving-power-of-your-library-card-8f490455.

[11] Institute of Museum and Library Services. “Public Libraries Survey, FY 2022.” https://www.imls.gov/research-evaluation/data-collection/public-libraries-survey. Also see the Library Search & Compare tool, which uses data from the Public Libraries Surveys, [12] and the Data File Documentation PDF, which includes some summary statistics from the FY 2022 survey. [13]

[12] Institute of Museum and Library Services. “Library Search & Compare | Institute of Museum and Library Services.” https://www.imls.gov/search-compare<https://www.imls.gov/search-compare

[13] Pelczar, Marisa, Jiayi Li, Sara Alhassani, and Sam Mabile. “Data File Documentation: Public Libraries in the United States Fiscal Year 2022.” Institute of Museum and Library Services, 2024, 3, I-1 to K-6 (PDF pages 9, 155-178). https://www.imls.gov/sites/default/files/2024-06/2022_pls_data_file_documentation.pdf.

[14] Tuttle, Brad. “22 Incredibly Useful Things Your Town Is Probably Giving Away for Free.” Money, May 25, 2016. https://money.com/free-stuff-lending-libraries/.

[15] Dankowski, Terra, and Brian Mead. “The Library of Things.” American Libraries, June 1, 2017. https://americanlibrariesmagazine.org/2017/06/01/library-of-things/.

[16] Shareable. “Shareable – About solidarity economy hub,” February 28, 2024. https://www.shareable.net/about/. Archived September 25, 2024: https://web.archive.org/web/20240925224403/https://www.shareable.net/about/.

[17] Kawano, Emily. “A Shareable Explainer: What Is the Solidarity Economy?” Shareable, May 2, 2024. https://www.shareable.net/a-shareable-explainer-what-is-the-solidarity-economy/.

[18] Llewellyn, Tom. “How Libraries of Things Build Resilience, Fight Climate Change, and Bring Communities Together.” Shareable, April 17, 2019. https://www.shareable.net/how-libraries-of-things-build-resilience-fight-climate-change-and-bring-communities-together/. Note: This article is part of a series of articles that was shared by WebJunction as a resource for information on libraries of things.

[19] Bautze, Alessandra. “How to Start a Library of Things Inside an Existing Library.” Shareable, March 10, 2020. https://www.shareable.net/how-to-start-a-library-of-things-inside-an-existing-library/. Note: This article is part of a series of articles that was shared by WebJunction as a resource for information on libraries of things. Alternatively, see PDF book. [20]

[20] Bautze, Alessandra. “How to Start a Library of Things Inside an Existing Library,” in Library of Things: A Cornerstone of the Real Sharing Economy, (Shareable, 2020), 47-48. https://www.shareable.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/08/2020-ebook-Library-of-Things-updated-8-3-20-1.pdf.

[21] Las Vegas-Clark County Library District. “I <3 Whitney Fresh Start – Las Vegas-Clark County Library,” http://web.archive.org/web/20240819120906/https://events.thelibrarydistrict.org/event/11617167 (archived August 19, 2024).

[22] Las Vegas-Clark County Library District. “Mobile Showers – Las Vegas-Clark County Library,” https://web.archive.org/web/20240914064152/https://events.thelibrarydistrict.org/event/11650582 (archived September 14, 2024).

[23] Whole Person Librarianship. “Map – Whole Person Librarianship,” August 16, 2019. https://wholepersonlibrarianship.com/map/.

[24] Norton, Stern, Meyers, DeYoung, “Understanding the Social Wellbeing Impacts,” 23.

[25] Horrigan, John B. “Libraries 2016.” Pew Research Center, September 9, 2016. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2016/09/09/libraries-2016/. Also see PDF: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/wp-content/uploads/sites/9/2016/09/PI_2016.09.09_Libraries-2016_FINAL.pdf (PDF page 4).

[26] Network of the National Library of Medicine [NNLM]. “HEALTH BYTES W/ Region 3 – Cultivating Protective Libraries (July 13, 2022).” YouTube, July 20, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OK9xU7PKiC4. Timestamp: [08:27].

[27] Norton, Stern, Meyers, DeYoung, “Understanding the Social Wellbeing Impacts,” 25.

[28] Klinenberg, Eric. Palaces for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life. New York: Crown, 2018, 45-46 (ebook pages).

[29] Vinovskis, Maris A. The Birth of Head Start: Preschool Education Policies in the Kennedy and Johnson Administrations. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005

[30] Vinovskis, The Birth of Head Start, 10.

[31] Vinovskis, The Birth of Head Start, 77-78.

[32] Sutherland, Paige, and Meghna Chakrabarti. “Censorship Wars: Why Have Several Communities Voted to Defund Their Public Libraries?” WBUR, September 8, 2022. https://www.wbur.org/onpoint/2022/09/08/censorship-wars-defund-public-libraries.

[33] Woodcock, Claire. “Texas Officials Would Rather Close Library than Stock Books They Don’t Like.” Vice, April 11, 2023. https://www.vice.com/en/article/texas-officials-would-rather-close-library-than-stock-books-they-dont-like/.

[34] Smith, Tovia. “Library Funding Becomes the ‘Nuclear Option’ as the Battle over Books Escalates.” National Public Radio, May 4, 2023. https://www.npr.org/2023/05/04/1173274834/book-bans-library-funding-missouri-texas-ashcroft.

[35] MacDonald, Ross. “The Small-Town Library That Became a Culture War Battleground.” The Nation, August 7, 2023. https://www.thenation.com/article/society/libraries-book-banning/.

[36] Kim, Elizabeth. “NYC Libraries to Get Budget Funding Back — And Reopen on Sundays.” Gothamist, June 27, 2024. https://gothamist.com/news/nyc-libraries-to-get-budget-funding-back-and-reopen-on-sundays.

[37] The New York Public Library. “Tell City Hall: No Cuts to Libraries! | the New York Public Library.” https://web.archive.org/web/20240627013811/https://www.nypl.org/speakout (archived June 27, 2024).

[38] The New York Public Library. “NYC’s Public Libraries Call for Reversal of $58.3m in Proposed Budget Cuts.” March 12, 2024. https://www.nypl.org/press/nycs-public-libraries-call-reversal-583m-proposed-budget-cuts.

[39] New York City Council. “NYC Council, Library Leaders, and New Yorkers Call on Mayor Adams to Restore Funding for Libraries at Rallies Outside of Branches Closed and Threatened by Budget Cuts.” June 23, 2024. https://council.nyc.gov/press/2024/06/23/2635/.

[40] Shera, Foundations of the Public Library, 216-218.

[41] Norton, Dowdall, “Strengthening Networks, Sparking Change,” 9.

[42] Network of the National Library of Medicine, “HEALTH BYTES W/ Region 3 – Cultivating Protective Libraries (July 13, 2022).” Timestamp: [19:42].